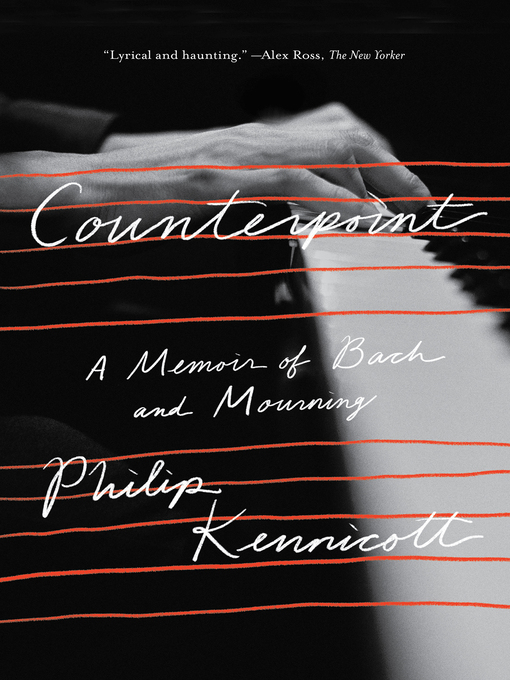

A Pulitzer Prize–winning critic's "lyrical and haunting" (Alex Ross, The New Yorker) reflection on the meaning and emotional impact of a Bach masterwork.

As his mother was dying, Philip Kennicott began to listen to the music of Bach obsessively. It was the only music that didn't seem trivial or irrelevant, and it enabled him to both experience her death and remove himself from it. For him, Bach's music held the elements of both joy and despair, life and its inevitable end. He spent the next five years trying to learn one of the composer's greatest keyboard masterpieces, the Goldberg Variations. In Counterpoint, he recounts his efforts to rise to the challenge, and to fight through his grief by coming to terms with his memories of a difficult, complicated childhood.

He describes the joys of mastering some of the piano pieces, the frustrations that plague his understanding of others, the technical challenges they pose, and the surpassing beauty of the melodies, harmonies, and counterpoint that distinguish them. While exploring Bach's compositions he sketches a cultural history of playing the piano in the twentieth century. And he raises two questions that become increasingly interrelated, not unlike a contrapuntal passage in one of the variations itself: What does it mean to know a piece of music? What does it mean to know another human being?